Something Fishy

An abridged extract from Bob Burton's Inside Spin: The Dark Underbelly of the PR Industry.

A hallmark tactic of activist campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s was the use of consumer boycotts to punish recalcitrant companies. By the 1990s, however, the trend was more towards developing standards and accrediting retail products that passed muster. The theory was that an accredited product would be rewarded by consumers while the laggards would be under financial pressure to lift their game. One of the pioneering projects during the 1990s was the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which was established by a broad coalition of non-profit groups. Its aim was to shift timber production to sources designated as more sustainable and reduce the market share for forest products derived from the destruction of the world's great forests. Despite numerous problems, the FSC label had some impact, especially in Europe.

A hallmark tactic of activist campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s was the use of consumer boycotts to punish recalcitrant companies. By the 1990s, however, the trend was more towards developing standards and accrediting retail products that passed muster. The theory was that an accredited product would be rewarded by consumers while the laggards would be under financial pressure to lift their game. One of the pioneering projects during the 1990s was the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which was established by a broad coalition of non-profit groups. Its aim was to shift timber production to sources designated as more sustainable and reduce the market share for forest products derived from the destruction of the world's great forests. Despite numerous problems, the FSC label had some impact, especially in Europe.

Fisheries were next. As Greenpeace in Europe stepped up its campaign against unsustainable fisheries, Unilever, which supplied approximately 25 per cent of the European and US demand for frozen fish, began to feel the heat. The company's Birds Eye and Iglo brands in particular were vulnerable to consumer pressure.10 Simon Bryceson, a consultant to the global PR firm Burson-Marsteller, advised Unilever that it should bypass Greenpeace and instead develop a partnership with the more 'conservative' WWF.11 Unilever and WWF split the US$1 million start-up costs, and in 1997 the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) was launched as a nonprofit organisation, headquartered in London. For Unilever, accreditation offered the prospect that it could marginalise Greenpeace and reassure skittish customers. As a trial run, the MSC drafted principles and criteria for assessing what constituted a 'sustainable' fishery. These were then tested against three small-scale fisheries, including the West Australian rock lobster fishery. All passed.

Following the trial accreditations, the MSC proclaimed to the world that a product that bore the MSC label would assure consumers 'that the product has not contributed to the environmental problem of overfishing'. However, instead of viewing itself as a tool for ensuring high environmental standards, the MSC wanted to position itself as being "precisely in the middle" of the fisheries management prescriptions advocated by environmentalists and the fishing industry.12 Once launched, the MSC needed some runs on the board. In the retail fish products market, the main game is in what is referred to as 'white fish' large-volume fisheries that can supply quality, white flesh for products such as fish fingers. Having set itself a target of having ten fisheries accredited before it could launch a major promotional blitz, the MSC needed high-volume fisheries accredited.

Following the trial accreditations, the MSC proclaimed to the world that a product that bore the MSC label would assure consumers 'that the product has not contributed to the environmental problem of overfishing'. However, instead of viewing itself as a tool for ensuring high environmental standards, the MSC wanted to position itself as being "precisely in the middle" of the fisheries management prescriptions advocated by environmentalists and the fishing industry.12 Once launched, the MSC needed some runs on the board. In the retail fish products market, the main game is in what is referred to as 'white fish' large-volume fisheries that can supply quality, white flesh for products such as fish fingers. Having set itself a target of having ten fisheries accredited before it could launch a major promotional blitz, the MSC needed high-volume fisheries accredited.

Turning a Blind Eye

Having teetered on the brink of financial collapse on more than one occasion, the MSC also desperately needed fisheries accredited in order to generate sufficient revenue from licensing fees. The New Zealand hoki, a fish with a long, silvery, tapering body that grows to well over a metre and can live for up to 25 years, was to be the first large-volume 'white fish' selected for MSC certification. The goggle-eyed hoki look sufficiently scary to ensure they are unlikely to ever feature in a full-colour WWF fundraising appeal. WWF had selected the New Zealand hoki fishery as one that would demonstrate the elegance of the MSC's arm's-length certification to deliver conservation outcomes via a corporate-friendly, but science-based, process. In 1999, WWF Australia established a project to promote the MSC in the region, proclaiming that certified products met 'stringent sustainability guidelines'.13 It had also landed a US$175,000 grant from the US-based David and Lucile Packard Foundation to facilitate its involvement in the process.

If WWF had a fairytale ending in mind, it wasn't to be. The hoki fishery relies on trawl nets, which can have a mouth opening 80 metres high and up to 400 metres long, big enough to swallow a skyscraper. Even though hoki are commonly found at depths of over 900 metres, New Zealand fur seals commonly become entangled when the nets are laid out or retrieved. Seabirds too, fall prey to the nets. The best estimates are that between 1989 and 1998, more than 5600 seals drowned in the industry's trawl nets. It was a major problem, with the population of the long lived mammals having already collapsed to approximately five per cent of their original number. The fishery also killed more than 1100 seabirds annually, including albatross and petrels, which are internationally recognised respectively as a vulnerable threatened species and a threatened species.With their populations already severely compromised, even the death of a few adult seabirds a year could prove devastating.

A coalition of fishing companies that owned the commercial quota for the hoki fishery formed the Hoki Fishery Management Company (HFMC) to apply for MSC accreditation. Part of the impetus for the HFMC's application was pressure from the German-based subsidiary of Unilever, Frozen Fish International, which bought supplied hoki to the European market. Accreditation held out the prospect that the NZ$300 million-a-year industry could rake in even more. The HFMC's application for certification was forwarded on to the Netherlands-based SGS Product and Process Certification, an MSC-approved consultancy. Despite finding that "the medium to long term impacts of hoki fishing on the ecosystem or habitats are not well understood at this time", SGS recommended the fishery be accredited, subject to what it described as "minor corrective actions".

The largest environment group in New Zealand, the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society—which is commonly referred to as Forest and Bird—was horrified, and argued against rewarding an unsustainable fishery. Behind the scenes, WWF New Zealand was worried too. In an internal email, the group's then Chief Executive, Jo Breese, expressed her alarm to the head of WWF International, Claude Martin, that accreditation would end up:

...compromising MSC, WWF and of course the hoki fishery. There are some very sensitive issues, e.g. 1000 fur seals killed per year, by-catch of seabirds and maintaining the fish stock. These could potentially 'blow up' in the media and be very damaging internationally to WWF, MSC and SGS. Also that Green Groups [sic] in NZ have the international networks to make this look very bad for MSC. At this stage it appears likely that we will not be able to support the certification process and outcomes. If we are asked by the media we will be forced to publicly criticise the process and possibly the outcomes...Which will inevitably reflect badly on MSC.14

Her plea got her nowhere.

A little over a week later, the MSC announced the accreditation of the fishery at a level of 250 000 tonnes per year, with minor qualifications. The then CEO of the MSC was upbeat, extolling the hoki accreditation as an "excellent example to other fisheries around the world."15 WWF New Zealand swallowed its pride, preferring to place its faith in promises of improved performance. In a joint media release with the fishing company and the MSC, the Washington D.C.-based head of WWF's Endangered Seas Program, Scott Burns, optimistically proclaimed his faith that the "corrective actions" would be adequate to resolve the identified problems.16 In a separate WWF statement, they were a little more cautious, stating only their "general support for the decision", subject to undertaking steps to "conserve seal populations."17 WWF, it seems, had a line for everyone. Against the din of applause from industry, government and WWF, the protests of Forest and Bird and other groups were drowned out.

Unilever quickly put the MSC's logo on its retail products and used the accreditation to introduce hoki into new European markets.18 Other companies extolled the marketing edge MSC accreditation would give hoki over other whitefish in the all important markets of Australia, Europe and the United States.19 WWF Australia's Director of Conservation, Ray Nias, was ecstatic about the financial benefits that flowed to the company from the accreditation. "The share price for the company", he gushed, "Sky rocketed because they gained access to markets in Europe."20

Forest and Bird thought the accreditation was so flawed that it decided to lodge an appeal. Eventually, the MSC-appointed panel agreed with Forest and Bird, concluding that there were "several" aspects of the accreditation "which would have justified a refusal of certification as at the date of the assessment."21 But instead of revoking the accreditation, the panel claimed that further tweaks would be sufficient to ensure that the fishery was in "good shape".

The hoki fishing industry, though, couldn't dodge ecological reality. The following year, the government bowed to scientific advice and cut the allowable catch of hoki to 220 000 tonnes. The following year, it was cut to 180 000 tonnes, but despite their best efforts, the industry could only catch less than three-quarters of that. In 2004, the allowable catch was slashed again, this time to 100 000 tonnes. As the fishery collapsed, fuelled in part by the legitimacy that went with the MSC label, the hope of a boom in export income vaporised. The cost to wildlife was staggering. One estimate was that in the first four years the fishery had been certified, approximately 3300 seals out of a total population of roughly 80 000 had been killed. In the same period, hundreds, possibly even thousands, of seabirds such as petrels and albatross were killed in the huge trawl nets, including some globally threatened species.

While WWF's primary mandate was to protect wildlife, in the five years after the accreditation, it remained publicly mute about the extraordinary impact of the hoki fishery on wildlife. Behind the scenes, WWF New Zealand participated in an Environmental Steering Group, established by HFMC, where it expressed its concerns that the 'corrective actions' were not being implemented and that not enough was being done to prevent seal deaths.22 "The first five years didn't go well", said Chris Howe for WWF New Zealand.23 WWF's preference for quiet diplomacy was not only ineffective, but did nothing to alert the hoki consuming public that they were being duped. It is even arguable that the MSC label on products in Australia containing hoki is contrary to the provisions of the Trade Practices Act, which bans misleading and deceptive conduct.While the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) allows eco-labelling schemes to make claims, this is only on the proviso that the "scheme's stated environmental criteria are met".24

Too Little, Too Late

In early 2006, the HFMC's proposal to extend certification for another five years, subject to only minor changes, was too much even for WWF. Jo Breese, CEO of WWF New Zealand, tentatively opposed recertification "at this time", but optimistically held out the prospect that necessary changes would be "achievable in the short term".25 Even so, the fishery was recertified, prompting WWF New Zealand to lodge an appeal. Despite being comprehensively rolled at every turn on the hoki fishery, WWF continues to be an MSC booster. In its 2006 annual report, WWF Australia brazenly states that it promotes "fisheries products that meet the highest environmental standards and give consumers a way to make a positive environmental choice". It is a sentiment WWF New Zealand echoes on its website. But, instead of WWF Australia informing its members of the collapse of the hoki fishery experiment, they proudly proclaimed that they were working with two fishing companies to have Australian mackerel icefish to be "the first sub-Antarctic fishery" accredited by the MSC.26

While WWF proclaim the MSC a success, independent reviews presented to the MSC Board argue otherwise. One, commissioned by three US foundations, concluded that the MSC's claim to certify 'sustainable' fisheries "in most cases is not justified", and fisheries "that are not in compliance with the law can be, and have been, certified".27 If WWF had helped collapse the hoki fishery without even being funded by the fishing industry, what would happen when big bucks were on offer?

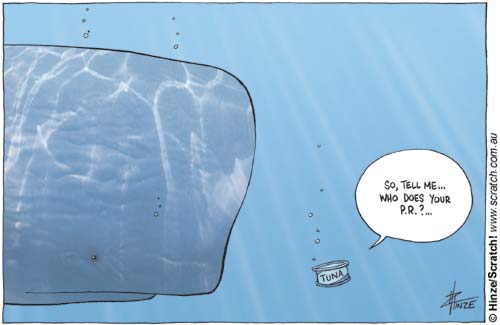

This is an abridged extract from Inside Spin: The Dark Underbelly of the PR Industry by Bob Burton, published by Allen & Unwin (Australia), A$24.95, ISBN 9781741752175 which is available from booksellers, as an ebook for US$17.45, or from Allen & Unwin. Inside Spin will be available in the US in April 2008. Footnotes cited in the text feature the original numbering from the book and can be viewed here. The illustration is by David Pope a.k.a. Hinze. His work can be viewed here.

Please help us document the work of WWF, the MSC, Unilever or Simon Bryceson or other groups or individuals mentioned in this article. You can become a SourceWatch volunteer contributor and add to or edit articles. It's free, easy and fun.