"Cash for Commentary" is Business as Usual

Conservative commentators Armstrong Williams, Maggie Gallagher and Michael McManus have been outed recently for taking money under the table to endorse Bush administration programs. These cases are only the tip of a much bigger iceberg, as you can tell from looking at the images I'm attaching here. I wrote about it three years ago in a story that described the work of conservative direct marketer Bruce Eberle, whose Omega List Company specializes in raising money using mail and e-mail.

Conservative commentators Armstrong Williams, Maggie Gallagher and Michael McManus have been outed recently for taking money under the table to endorse Bush administration programs. These cases are only the tip of a much bigger iceberg, as you can tell from looking at the images I'm attaching here. I wrote about it three years ago in a story that described the work of conservative direct marketer Bruce Eberle, whose Omega List Company specializes in raising money using mail and e-mail.

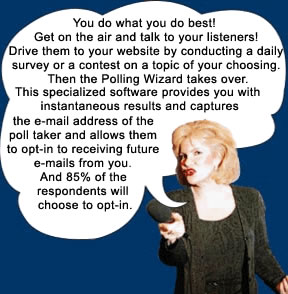

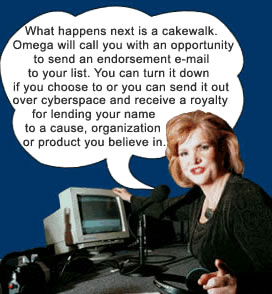

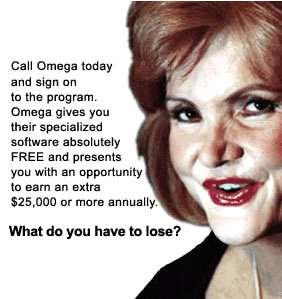

On a section of the website that has subsequently been removed, Omega List was quite straightforward about the fact that it pays conservative commentators to endorse clients and their causes. A series of web pages featured conservative radio show host Blanquita Cullum explaining exactly how the system works and how other radio hosts could get in on the gravy. "You do what you do best!" she said. "Get on the air and talk to your listeners! Drive them to your website by conducting a daily survey or a contest on the topic of your choosing." Eberle's "polling wizard" software, installed on the site, would then capture the names of respondents so that they could be hit up for money. "What happens next is a cakewalk," Cullum continued. "Omega will call you with an opportunity to send an endorsement e-mail to your list ... and receive a royalty for lending your name to a cause, organization or product you believe in. ... Omega gives you their specialized software absolutely FREE and presents you with an opportunity to earn an extra $25,000 or more annually."

In addition to Omega List and Blanquita Cullum, there's also the instructive example of media mogul Conrad Black, whose financial unraveling provided yet another example of the way people with money can collect conservative pundits the way other people collect stamps or autographs -- a story that John Stauber and I examined in our 2004 book, Banana Republicans. Black, a British lord, was CEO of Hollinger International, a media conglomerate whose holdings included more than a hundred newspapers around the world such as the Chicago Sun-Times, the Daily Telegraph and Spectator newspapers in London, and the Jerusalem Post. Black himself sat on the board of directors of two think tanks—the Hudson Institute and the Nixon Center. His resignation from Hollinger in December 2003 occurred after the company fell into financial crisis, prompting minority shareholders to form an investigative committee, which found more than $32 million in payments that "were not authorized or approved by either the audit committee or the full board of directors of Hollinger."

In addition to Omega List and Blanquita Cullum, there's also the instructive example of media mogul Conrad Black, whose financial unraveling provided yet another example of the way people with money can collect conservative pundits the way other people collect stamps or autographs -- a story that John Stauber and I examined in our 2004 book, Banana Republicans. Black, a British lord, was CEO of Hollinger International, a media conglomerate whose holdings included more than a hundred newspapers around the world such as the Chicago Sun-Times, the Daily Telegraph and Spectator newspapers in London, and the Jerusalem Post. Black himself sat on the board of directors of two think tanks—the Hudson Institute and the Nixon Center. His resignation from Hollinger in December 2003 occurred after the company fell into financial crisis, prompting minority shareholders to form an investigative committee, which found more than $32 million in payments that "were not authorized or approved by either the audit committee or the full board of directors of Hollinger."

By January, the investigation had uncovered more than $200 million in dubious transactions, prompting the company to file a lawsuit against Black, alleging that he had "diverted and usurped corporate assets and opportunities from the Company through systematic breaches of fiduciary duties owed to the Company and its non-controlling public shareholders." The "systematic breaches" included "excessive, unreasonable and unjustifiable fees" paid from Hollinger to another company owned by Black, as well as other irregularities and "sham transactions." They also involved other tangled financial dealings reflecting what the New York Times described as a “seemingly porous boundary among Lord Black’s social, political and business lives.”

Prior to his fall from grace, Black had built a reputation for himself as a deep thinker in his own right, publishing a thick biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt, its dust jacket decorated with laudatory blurbs from conservative intellectuals including Henry Kissinger, columnist George F. Will, and National Review founder William F. Buckley, Jr. "What the blurbs did not mention was that each man was praising the work of a sometime boss,” the Times reported. "During the 1990’s, Lord Black had appointed all three to an informal international board of advisors of Hollinger International, the newspaper company he controlled. For showing up once a year with Lord Black to debate the world’s problems, each was typically paid about $25,000 annually." In addition to Buckley, Kissinger and Will, Black’s advisory board included luminaries such as former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Richard Perle, the former assistant secretary of defense to Ronald Reagan.

Prior to his fall from grace, Black had built a reputation for himself as a deep thinker in his own right, publishing a thick biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt, its dust jacket decorated with laudatory blurbs from conservative intellectuals including Henry Kissinger, columnist George F. Will, and National Review founder William F. Buckley, Jr. "What the blurbs did not mention was that each man was praising the work of a sometime boss,” the Times reported. "During the 1990’s, Lord Black had appointed all three to an informal international board of advisors of Hollinger International, the newspaper company he controlled. For showing up once a year with Lord Black to debate the world’s problems, each was typically paid about $25,000 annually." In addition to Buckley, Kissinger and Will, Black’s advisory board included luminaries such as former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Richard Perle, the former assistant secretary of defense to Ronald Reagan.

Most of these illuminati had received payments of more than $100,000 over the years but hadn’t felt compelled to disclose the payments when they publicly praised or disseminated Black’s political views. During the buildup to war with Iraq, for example, George Will had written a column praising a hawkish speech that Black gave in London. After the New York Times called to ask if he should have disclosed his financial relationship with Black at the time, Will snapped, "My business is my business. Got it?"

Buckley was a bit more polite but equally evasive. When Black’s financial scandal began making the news in November 2003, Buckley had written a defense of the embattled mogul, calling him "extraordinarily learned, profoundly instructed, modest in demeanor, eloquent in speech and in kindnesses." Responding to editorial criticism of Black in the New York Observer, Buckley blasted the editorial as "febrile with hate" and added, "Since your mind inclines in that direction, hear this: he has never donated a nickel to any of my enterprises."

Technically, that might have been true, since the money Buckley received over the years was payment for services, not a "donation." But it was a lot more than a nickel. When queried by the New York Times, Buckley estimated that Black had paid him at least $200,000.

So what's the difference between pundits like Blanquita Cullum or William F. Buckley, as compared with Armstrong Williams, Maggie Gallagher and Michael McManus? One difference, of course, is that Williams, Gallagher and McManus were bribed by the government rather than by a private client. Some people may feel that it's worse somehow if the propaganda beamed at their brains is funded by their own tax dollars.

As far as journalistic ethics are concerned, however, that's not much of a difference. In all of the cases I've listed above, the pundits in question took money from someone whose interests they were plugging and didn't disclose the payments to their audience. The code of ethics of the Society of Professional Journalists is very clear that this is unacceptable. It states that journalists should "Avoid conflicts of interest, real or perceived. Remain free of associations and activities that may compromise integrity or damage credibility. Refuse gifts, favors, fees, free travel and special treatment, and shun secondary employment, political involvement, public office and service in community organizations if they compromise journalistic integrity. Disclose unavoidable conflicts. ... Deny favored treatment to advertisers and special interests and resist their pressure to influence news coverage."